What does an evidence-based energy transition look like? | By Science Communicator and Author, Zion Lights.

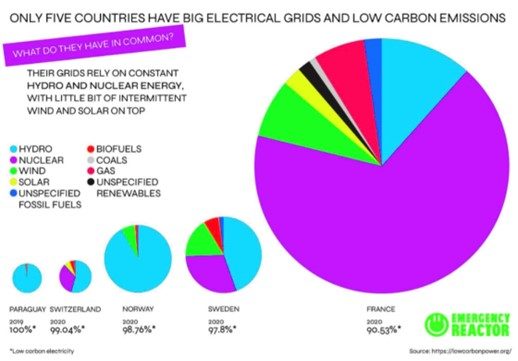

OPINION | Do you know what a low carbon grid looks like?

It probably looks different to what you expect.

Unfortunately, few countries are geographically suited to producing large amounts of hydropower, and while intermittent renewables can be added to the grid to provide some of our energy needs, the data points are clear: we need to build more nuclear power plants for baseload power generation.

There’s also the problem of the inclusion of biomass in renewables figures around the world. Burning wood to create energy is archaic and bad for the planet. Biofuels should not be classed as renewable.

While climate activists grab media headlines with arguments to just stop oil, too little discussion centres on the alternatives to oil and other fossil fuels. Usually, nuclear energy is the elephant in the room, and when it is mentioned it’s often by an opposing voice.

Yet there is scientific consensus that we need nuclear power to address climate change. Nuclear energy is included in all of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) pathways for decarbonisation in its landmark 1.5°C report. This is alongside carbon capture technology and measures to reduce energy like insulating buildings.

Bizarrely, opponents of nuclear energy are still permitted a seat at the table for discussions of energy even though their perspective is no different to offering someone who is anti-vaccination a seat alongside doctors.

Nuclear energy saves lives: research by leading climate scientist James Hansen finds that it has saved more than two million people from early deaths due to air pollution produced by burning fossil fuels. And the clean energy it has generated has saved 64 gigatonnes of greenhouse-gas emissions – around two years’ worth of total global emissions – which would have been produced by the burning of fossil fuels.

The most common objection to nuclear energy is its waste, or spent fuel. Whilst this is indeed hazardous it is managed with rigorous safety and doesn’t harm anyone. Meanwhile, we dump waste from burning fossil fuels into the Earth’s atmosphere, polluting the air we breathe and killing millions of people a year through air pollution – an estimated one in five deaths worldwide according to Harvard University research.

Nuclear has the smallest land footprint of all energy sources, which is an important consideration in a small country like Britain where land is limited.

Nuclear also confers energy security, which events of the last year have shown the need for. Indeed France’s nuclear fleet was built as a response to the oil price shocks of the early 1970s following the war in the Middle East.

It is often claimed that nuclear energy is too expensive, often in comparison with Levellised Cost Of Energy (LCOE) figures (e.g. Lazard) for wind and solar, but these comparisons omit the costs of building storage, interconnects, demand-management systems or other means of providing low carbon energy reliably, 24/7. Nuclear power plants also have a far longer lifetime than wind and solar farms; 40-80 years compared to 15-25.

Nuclear energy can also be cheaper for the consumer: In 2019 France’s electricity, 71% of which came from nuclear energy, cost just 59% of that in Germany, which had been shutting down nuclear power since 2011 and is now mining for more coal.

These points are rarely factored into discussions of cost. Meanwhile, the total cost of climate change damages to the UK is projected to increase from 1.1% of GDP at present to 3.3% by 2050 and 7.4% by 2100.

Another criticism is the time taken to build nuclear power stations, but a 2016 analysis found that of the 441 reactors then in operation around the world 18 were completed in just three years: twelve in Japan, three in the US, two in Russia and one in Switzerland, with a mean construction time globally of 7.5 years. Research into construction technology is informing practice such as at Hinkley Point C, and the skills and supply chains built for the first reactor streamline construction of subsequent units. The UK could become as much a leader in nuclear construction as it has become in offshore wind development, if it continues to deploy these skills and hold on to skilled workers who are assured of jobs working on new reactors.

Young people are experiencing high levels of eco-anxiety alongside financial concerns over their futures. If we don’t want them to block roads, we should be urging them towards well-paid, unionised, clean jobs building and operating nuclear power plants instead. After all, there are few better ways to actively help mitigate the climate emergency.

*See all recent Climate Perspectives editions here.